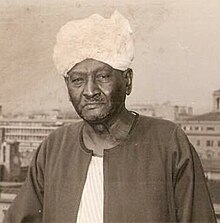

Abdallah al-Fadil al-Mahdi (Arabic: عبد الله الفاضل المهدي; 1890 – 18 May 1966) was a Sudanese statesman and key figure in Sudan's path to independence by playing an important role in the "Gentlemen's Agreement" with Egypt in 1952, enabling Sudan's self-government and self-determination. Abdallah was a National Umma Party member. He resisted Ibrahim Abboud's rule, and after October 1964 revolution, he served on the Sudanese Sovereignty Council and was instrumental in establishing a mosque in the Republican Palace. Abdallah married twice and emphasised education for his children.

Abdallah al-Fadil al-Mahdi | |

|---|---|

عبد الله الفاضل المهدي | |

| |

| Member of the Sovereignty Council | |

| In office 10 June 1965 – 18 May 1966 | |

| President | Ismail al-Azhari |

| Prime Minister | Muhammad Ahmad Mahgoub |

| Preceded by | Sovereignty Council (1964–1965) |

| Succeeded by | Gaafar Nimeiry |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1890 Omdurman, Mahdist State |

| Died | 18 May 1966 (aged 75–76) |

| Political party | National Umma Party |

| Spouses | Umm Al-Kiram Sharif (m. 1914)Munira Al-Qabbani (m. 1936) |

| Education | Gordon Memorial College (no degree) |

Early life and education

editAbdallah al-Fadil al-Mahdi was born in 1890 in Omdurman, Mahdist State. His mother was Zainab Muhammad Ibrahim Fung was a descendant of the Funj sultanas. Her grandfather, Ibrahim Fung, was one of the Funj princes who lived in Al-Qatina. Her mother was Fatima bint Abdul Rahman, the granddaughter of Mek Ajeeb Al-Manglik. Abdallah's mother immigrated with Caliph Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, after the Battle of Shakaba incident which resulted in her husband, Al-Fadil, and Caliph Muhammad Sharif death. She migrated to the Al-Duwaym with her three children, and then her son Muhammad and her daughter died due to an illness that afflicted them. She and Abdallah then settled in Al-Qatina and got married.[1]

Abdallah completed the khalwa and primary school under the care of his maternal uncle, Sirr Al-Khatim, after which Imam Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi (his uncle) came and took him o Omdurman.[1] As part of the Anglo-Egyptian government's efforts to encourage enrolment of Mahdist boys in schools in Omdurman and Wad Medani, as well as the Gordon Memorial College, they typically received admission free of charge and were provided with school uniforms. However, in 1914, while Abdallah was still in the third grade at the primary school within the Gordon College, the Director of Education recommended his transfer. His recommendation, stated, "I think it is in the boy's interest that he should turn his attention to agriculture and cultivation of his lands in the Gezira Aba. His character is very good but he is not clever. I propose therefore to send him to Tokar to undergo a course of agricultural instruction."[2][3] Abdallah completed his secondary education in Tokar.[1]

Abdallah grew interested in agriculture and had Egyptian and foreign advisors, especially from Italy, to develop agriculture in Sudan. He worked to develop agricultural work by importing agricultural equipment from abroad.[1]

Political career

editSudanese independence

editAbdallah is considered the architect of the Gentleman's Agreement in which Egypt decided to remain neutral and which it later reneged on. His good relationship with Egypt played an important role in Sudan's attainment of its full rights, especially since there was trust between him and Major General Muhammad Naguib.[1][4][5]

On 19 October 1952, an agreement was reached between the Egyptian Government and Abdallah al-Fadil al-Mahdi of the Sudanese Independence Front. This agreement gave the green light for Sudan to achieve self-government by the end of 1952, followed by the exercise of the right to self-determination within the subsequent three years.[6] The agreement came to be known as the "Gentlemen's Agreement".[7]

The agreement called for the establishment of a committee consisting of a representative from Egypt, one from Britain, two Sudanese members, and a fifth member from a neutral nation, possibly India or Pakistan. This committee's primary purpose was to provide guidance and advice to the Governor-General in the discharge of his duties. It also expanded the reach of direct elections by including 35 additional constituencies, fostering a more representative political process. In addition, the agreement envisioned the establishment of an international commission tasked with overseeing the electoral processes within Sudan, ensuring fairness and impartiality. Lastly, it laid the groundwork for a "Sudanization Committee" with the specific aim of expediting the replacement of foreign personnel with Sudanese individuals across various sectors, including administration, the police force, and other public appointments.[6] The agreement also dealt with Nile water.[7]

After independence

editAbdallah was one of the Imam Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi senior assistant,[1] and member of the National Umma Party (NUP) executive committee.[8] He built bridges within the political movement, Sufi orders, and clerics. He later refused to assume the Imamate of the Ansar despite his entitlement to it and passed it to Sadiq al-Mahdi. In 1962, he founded the first Sudanese company to help with Hajj.[1]

Abdallah was a member of the Sudan's Legislative Assembly. He played a role in resisting Ibrahim Abboud's rule, which sparked the Mawlid incident. He later helped in stopping the bloodshed between the Ansar and the government which led to the release of Imam Saddik al-Mahdi.[1]

Sovereignty Council

editAbdallah was a member of the Sudanese Sovereignty Council from 10 June 1965 until his death on 18 May 1966. The council came after the general parliamentary elections in 1965, the third in the history of Sudan, as it replaced another Sovereignty Council, which was managing the country’s affairs for a transitional period after the overthrow of the rule of Lieutenant General Ibrahim Abboud. This Sovereignty Council consisted of five members, and its members were amended twice. The Chairman of the Sovereignty Council was Ismail al-Azhari.[9] During Abdallah tenure, he joined the first line-up which came to power from 10 June 1965, and it was composed of Ismail al-Azhari (Democratic Unionist Party), and Khader Hamad (DUP), Abdullah al-Fadil al-Mahdi (NUP),[10] Abdel Halim Mohamed (NUP), and Luigi Adwok Bong Gicomeho (Southern Front) who resigned in 14 June 1965 and was replaced by Philemon Majok.[9][11][12]

Abdallah is credited with establishing a mosque in the Republican Palace during his membership in the Sovereignty Council.[1]

Personal life and death

editAbdallah married Umm Al-Kiram Sharif in 1914, and together they had 8 children including Kamal,[1] who was the Justice and Public Works minister in 1968.[13] In 1936, he married Munira Al-Qabbani, and together they had 6 children including Mubarak,[1] who was the Minister of Industry in 1987.[14] Abdallah was keen on educating his children in schools and universities inside and outside Sudan.[1]

He died on 18 May 1966.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Al-Mahdi, Bakhita Al-Hadi (2021-05-19). "في الذكرى 48 لوفاة السيد عبد الله الفاضل المهدي بخيتة الهادي المهدي" [On the 48th anniversary of the death of Mr. Abdullah Al-Fadil Al-Mahdi]. Al-Ttahrer. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ Ibrahim, Hassan Ahmed (2004-01-01). Sayyid ʻAbd Al-Raḥmān Al-Mahdī: A Study of Neo-Mahdīsm in the Sudan, 1899-1956. BRILL. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-04-13854-4.

- ^ Sudan Notes and Records. 1974.

- ^ Fisher, Sydney Nettleton (1959). The Middle East: A History. Knopf.

- ^ "مبارك الفاضل يطالب بإطلاق اسم عبد الله الفاضل المهدي على شارع هذا الشارع (...) - عزة برس" (in Arabic). 2021-12-18. Retrieved 2023-09-11.

- ^ a b "Developments of the Quarter: Comment and Chronology". Middle East Journal. 7 (1): 58–68. 1953. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322464.

- ^ a b Warburg, Gabriel (1992). Historical Discord in the Nile Valley. Hurst. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-1-85065-140-6.

- ^ "Developments of the Quarter: Comment and Chronology". Middle East Journal. 7 (4): 504–519. 1953. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322544.

- ^ a b "Heads of State". Zarate. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ^ Mideast Mirror. July 1965.

- ^ "Daftar Presiden Sudan | UNKRIS | Pusat Ilmu Pengetahuan". p2k.unkris.ac.id. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ "Obituary: Abdel Halim Mohammed Abdel Halim" (PDF). Brit.med.J. 2009.

- ^ Africa Special Report: Bulletin of the Institute of African American Relations. The Institute. 1968.

- ^ Banks (red.), Arthur Sparrow (1987). Political handbook of the world: 1987 : governments and intergovernmental organizations as of March 15, 1987 : (with major political developments noted through June 30, 1987). CSA Publications. ISBN 978-0-933199-03-3.

External links

edit- Al-Mahdi, Tayeb (2016-05-18). السيد عبدالله الفاضل المهدي الرمز والاثر [Mr. Abdullah Al-Fadil Al-Mahdi, the symbol and the impact] (Videotape).