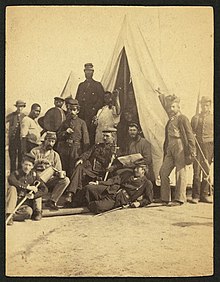

The 79th New York Infantry Regiment was a military regiment organized on 20 June 1859, in the state of New York. Prior to the American Civil War it was one of the three regiments which formed the Fourth Brigade of the First Division of the New York State Militia. The 79th gained fame during the American Civil War for its service in the Union Army.

| 79th New York Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1858 – 1876 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Highland Regiment |

| Size |

|

| Part of |

|

| Nickname(s) | Highland Guard, Cameron Highlanders, Cameron Rifle Highlanders |

| Colors | Cameron of Erracht tartan |

| Anniversaries | Main anniversary on 13 May starting in 1866 with quarterly meetings held. |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

|

| Insignia | |

| IX Corps (1st Division) badge |  |

| IX Corps (3rd Division) badge |  |

Organization and pre-civil war

editThe 79th New York was established in the fall of 1858 in response to the State of New York requiring the 2nd New York to conform to the new uniform regulations. The Highland Guard/79th New York was created with the help of the St. Andrews and Caledonian societies of New York and wealthy financial backers like Samuel M. Elliot and Roderick W. Cameron. The New York Militia organization had no connection to the 79th Cameron Highlanders of Scotland, but was recruited from British Army veterans of the Scottish Regiments living in the United States. Similarly to the Queens Own Cameron Highlanders, the 79th Regiment wore the Cameron of Erracht tartan kilt as part of their uniforms until midway through their service in the American Civil War.[2]

The 79th New York (348 strong Spring 1859) was part of 1st Division, 4th Brigade of the New York Militia, the regiment was designated as light infantry cross trained train [clarification needed] as heavy artillery for the defense of Manhattan and also provided parade and guard for dignitaries such as the Prince of Wales and the Japanese ambassador when they visited Manhattan[clarification needed].

The 79th, without knowing it, set themselves up to take part in nearly every major engagement of the civil war and become one of the most known and traveled regiments in the Union Army.[citation needed]

Uniform

editWhen the organization had their first drill on 25 October 1858, the men were in civilian clothing as uniforms were not yet available. As per the guide lines set by the New York Militia, the Highland Guard was to uniform their soldiers in tartan trousers, not kilts. The inspector was informed by Col. McLeays that:

"Their stuff for trousers was expected to arrive from Scotland daily, when they would immediately put their uniforms under contract for manufacture". Report of inspection, 4th Brigade, NYSM, 25 October, in annual report of the AG, NYS, (1858) The issued uniform as per the New York State Militia agreement consisted of these items:

Highland Cut Coat

The Highland Cut Coat was dark indigo blue wool broadcloth with applied false red cuffs and a blue collar which were trimmed with red facings with a small white piping line behind the red facing. The coat was trimmed with red wool spun cording on the edges of the coat body and around the circumference of the cuffs midway of the red cuff facing. It had 18 (New York State) buttons in all with 9 2.20 cm (7/8 in) buttons down the front and two on the rear and 3 1.50 cm (5/8 in) buttons on each cuff, 1 1.50 cm (5/8 in) button on the left hip for the belt loop. The jacket was lined in tan polished cotton with quilting in the front panels that extended over and onto the back of the shoulders, following the breast panels. The flaps were lined with red wool or red polished cotton. (Two different materials used on both of the two pre-war jackets still known to exist.)

Tartan Trousers

Cameron of Erracht trousers in the large military sett with a tartan repeat of nine inches. The tartan was matched and had Victorian trousers cut to them consistent with common trousers of the late 1850s.

Glengarry Bonnet

The glengarry was knit and felted as one cover. Dicing and body as one piece. It was dark blue with dicing that were red, blue and white, in two rows high that was off set by one square to the right. The glengarry was lined in black polished cotton and while some of the originals that still exist today have quilting and other lining decorations, three of five have different lining treatments.

Leathers

The belts used were common M1839 "baby US" belts that were 1.5 inches. Also used were Springfield bayonets and scabbards with the various models of .69 weapons, shield pattern cap pouches, and the M1857 cartridge box.

Parade uniform

When on parade the 79th wore the kilt, going against the wishes of the New York Militia.

This uniform used the same jacket and glengarry but instead of trousers made of tartan, they had New York tailors make non-regulation kilts.

Kilts

The kilts were made of the same Cameron of Erracht. They were not pleated to the line as is common in Scottish military regiments, but to the sett as seen in civilian kilts. The kilts were very odd and unlike kilt before or since thanks to their unqualified manufactures. They were box pleated, and used two tartan straps that buckled into suspender buckles on either hip. Because of their lack in size variation, suspenders were worn with them.

Original kilt information: http://emuseum.nyhistory.org

Sporran

The sporran was made of wavy white horse and or goat hair with three black tassels with a black leather cantle.

Original glengarry information: http://emuseum.nyhistory.org

Hose and flashes

Common Victorian red and white diced hose with common Victorian flashes.

Shoes

Low cut false buckle shoes

Civil war

editDeparture for federal service

editSgt. Robert Gair of 3rd Company recalled that the 79th was at a drill when news of the firing on Ft. Sumter came across the telegraph. The Regiment held a formation an unanimously voted to offer their services to the Governor of the state and President Lincoln. The 79th's 6 companies had approximately 300 on the muster rolls - common for a militia regiment at the time, but understrength for the regulation of 1,000 men. The 79th recruited 600 additional men in the weeks between mid April and early May when the Regimental mustered into service on May 13. Camped in Central Park, the Highlanders waited for orders from the 1st Division 4th Brigade, N.Y.S.M. to move to Washington.

On 2 June 1861, the Highland Guard, 895 men strong, marched down Broadway on its way to Washington. Passing through Baltimore, the Highlanders received a good welcome—in contrast with the reception the 6th Massachusetts Militia had received a few days earlier. After arriving in Washington, the regiment elected James Cameron, the brother of Simon Cameron, President Lincoln's Secretary of War as its Colonel. The Regiment was quartered at Georgetown College, recently vacated by the 69th N.Y.S.M, and spent their first few couple weeks in Washington filling their time with drill and guard mounts. The 79th was moved from Georgetown College to a camp on Maridian Hill overlooking the city. The camp was their first experience with life in tents. Early July saw a moved from the City across the chain bridge into Virginia. Singing "All the Blue Bonnets are Over the Boarder", the Highlanders crossed the Promoac and settled in a placed they named "Camp Weed". They were attached to Sherman's Brigade, Tyler's Division, in McDowell's Army of Northeastern Virginia,[3] for the advance on Manassas.

First Bull Run

editAt the First Battle of Bull Run on 21 July 1861, the Third Brigade of Tyler's First Division, under Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman, consisted of four regiments of infantry (2nd Wisconsin, 13th, 69th, and 79th New York) and a battery of artillery, the 3rd United States Artillery, Company E. The 79th New York experienced some of the fiercest fighting and suffered some of the highest Union casualties at First Bull Run (referred to by the Confederates as First Manassas) although, to begin with, it appeared that they would miss the action. As Confederates fled from the initial Union attack and withdrew up the hill past the Henry House, Private Todd stepped out of line calling to Colonel Sherman, "Give us a chance at 'em before they get away". His sergeant, a British Army veteran, dragged him back into line, growling "shut up your damned head - you'll get plenty of chance before the day is over".

Sherman, in obedience to orders, committed his regiments piecemeal to the capture of Henry House Hill. He first sent the 2nd Wisconsin who, still wearing their militia gray uniforms, were shot to pieces by both sides. When the Wisconsin boys were eventually driven back, the 79th were ordered forward. Led by their colonel, James Cameron, they charged three times over the dead and wounded of the 2nd Wisconsin. Unluckily, in the smoke of battle, they mistook a Confederate flag for one of their own and ceased firing. It was a costly mistake - "As we lowered our arms and were about to rally where the banner floated we were met by a terrible raking fire, against which we could only stagger". Retreating back down the hill they saw Colonel Cameron lying dead in the yard of the Henry House. He had been killed by the Confederates' second volley.

The Highlanders eventually retreated from the plateau and sank sullenly behind the brow of the hill to nurse their wounds. There they remained for two more hours while the attack was pressed by other Union regiments with an equal lack of success, until all were finally driven from the plateau by Confederate reinforcements. It then acted as a rear guard during the Federals' ignominious retreat to Washington. The regiment sustained one of the heaviest losses of the battle, losing 32 killed, including their commanding officer, 51 wounded (eight mortally) and 115 captured (including Capt. James A. Farrish of Company B who was wounded) or missing—a total of 198 - 22 percent of its strength.

On their return to Washington, following the First Battle of Bull Run, the Highlanders, having sustained one of the highest number of casualties among Union regiments engaged in the battle, were employed building defences around the capital, helping to construct a series of forty-eight forts and other defences plus 20 miles of trenches. The whole project had to be carried out with just picks and shovels. It was backbreaking work; one of the men recalled it as "the hardest kind of manual labor." "Spades were trumps" quipped one New Yorker "and everyman held a full hand"

On the morning of 14 August 1861, the Highlanders, together with the 13th and 21st New York volunteer infantry regiments, mutinied and demanded an adjustment of certain perceived grievances. The men felt tricked when the three-month volunteers were allowed to return home while they, three year-volunteers who had performed their duties equally well, were not permitted to return to New York. They were further incensed that they were unable to quit the army, unlike their officers who had the privilege of being able to resign their commissions. They also objected to having a new colonel, Isaac Ingalls Stevens, appointed on 30 July to replace James Cameron (killed at First Manassas), rather than being able to elect their own commander as was the custom with militia units. The situation was exacerbated by a shortage of junior officers brought about by wounds, capture or resignation. In just over a month, the regiment had lost its colonel, major, nine of its 10 captains and a number of lieutenants. Fueled by alcohol, the men finally refused to carry out any further duties.

These fledgling soldiers were undoubtedly naive as to the seriousness of their actions, believing that, as freemen, they could exercise their democratic right to do whatever they saw fit. They were quickly disabused of these unmilitary notions when Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, blaming the regiment's own officers for allowing the unrest, appointed a regular army officer with orders to mow the mutineers down if they did not immediately surrender. A battalion of regular infantry, supported by a squadron of regular cavalry and a battery of artillery, was lined up facing the 79th, firearms loaded and ready for use. When the mutineers, who had not anticipated such a response to their complaints and whose own arms were stacked, were ordered to cease their mutiny, they recognised the futility of their position and speedily submitted. The whole matter was handled quickly and efficiently and was a most salutary example to any other regiment that might consider similar disobedience. Twenty-one members of the 79th who were considered to be the ringleaders of the revolt were sent to the military prison at Fort Jefferson, Florida, on the Dry Tortugas, Florida, and the 79th's regimental colours were taken away, which McClellan then kept in his own headquarters until the regiment redeemed itself some months later.

A contemporary account in the publication Harper's Weekly noted, "The scene during the reading of the order of General McClellan was exceedingly impressive. The sun was just going down, and in the hazy mountain twilight the features and forms of officers and men could scarcely be distinguished, Immediately behind his aide was General Porter, firm and self-possessed. Colonel Stevens was in front of the regiment, endeavoring to quiet his rather nervous horse. In the rear of the regulars, and a little distance apart, General Sickels sat carelessly on horseback, coolly smoking a cigar and conversing with some friends. At one time during the reading a murmur passed through the lines of the mutineers, and when the portion of the order directing the regiment to surrender its colors was read a private in one of the rear lines cried out in broad Scotch tones, "Let's keep the colors, boys!" No response was made by the remainder of the regiment. Major Sykes at once rode up the line to where the voice was heard. It would have been more than the soldier's life was worth had he been discovered at the moment in pistol range by any of the officers."

Early 1862

editThe regiment took part in the expedition to Port Royal Ferry in January 1862 and saw action at Pocotaligo, South Carolina, in May, but not before becoming part of the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division of the Department of the South in April.

In June, the Highlanders were part of the expedition to James Island and took part in the Battle of Secessionville, where Brigadier General Henry W. Benham, who was in temporary command of the Union forces, ordered a bloody and foolhardy assault on the Confederate positions. Instructed not to undertake any offensive operations Benham, over the objections of his Division commanders, ordered a futile attack on Confederate general, N. G. "Shanks" Evans.

The position was surrounded by a swamp and defended by rifle pits. Although first attack was made by the 8th Michigan, whose history was closely intermixed with the 79th, the two regiments sharing a mutual respect and close friendship, swapping hats and playing pranks with each other. So close was their comradeship, the two regiments were often referred to as the "Highlanders" and the "Michilanders."

The 8th Michigan's assault was cut down by a murderous fire before reaching the enemy lines and the 79th, moving to their support, fared no better. Trapped, without reinforcements, the Highlanders were forced to retreat across open ground. Three futile assaults had been made with the loss of 683 Union soldiers, while the defenders lost only 204. The Highlanders alone lost 110 men out of 474 engaged, but their bravery was recognised by the Confederate Charleston Mercury, which said, "Thank God Lincoln had only one 79th regiment." Brigadier General Benham was relieved of command, arrested for disobedience of orders, and his appointment revoked by Lincoln.

On 12 July the regiment began its transfer to Newport News, Virginia, where it arrived on the 16th to become part of the 9th Army Corps, Army of the Potomac.

Second Bull Run and Chantilly

editIn August 1862, the regiment was involved in Pope's Campaign in Northern Virginia and, just a year after the death of James Cameron at Bull Run, the regiment was once again fighting over the same battlefield. Manassas was once again to prove unlucky for the 79th as their colonel, Addison Farnsworth, also commanding the First Brigade, was wounded.[4] Lt. Colonel Morrison, returning from a wound received at Seccessionville, was put in command of the brigade.[5] At Chantilly on 1 September 1862, while approaching the crossroads of the Warrenton and Little River turnpikes, the Union forces collided with Stonewall Jackson's men who were formed in a line in front of Ox Hill facing southeast near Chantilly Mansion.

In the ensuing battle, Cameron's successor as regimental commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Isaac Ingalls Stevens, now in command of the division, led his old regiment for one last time. Under an overcast sky, which threatened rain, Stevens organised the 79th into three lines and took them into the attack. As they advanced across the blood soaked battlefield he ran past the body of his own son, who lay critically wounded. Calling "Follow me, my Highlanders" Stevens was killed instantly by a bullet through his temple as he took the regiment colors from the sixth color bearer to fall. He died amid the cheers of victory with the color staff gripped firmly in his hand almost at the same time and nearly on the same ground as Major General Philip Kearny.

The primary opposing unit faced by the 79th was the 6th Louisiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment of Louisiana Tigers fame, led by Irish-born Major William Monaghan. The 6th Louisiana was the most thoroughly Irish of all the Tiger regiments, with the result that the battle in a raging thunderstorm devolved into Celt-on-Celt, hand-to-hand combat, and eventually sputtered to an indecisive end in rain and darkness. A survivor with the Confederate troops said, "We camped on the field, sleeping side by side with the dead of both armies. It was very dark; occasionally the moon would come from under a cloud and show the upturned faces of the dead, eyes wide open seeming to look you in the face."[6]

The Highlanders had sustained heavy losses— nine men were killed, 79 wounded (one mortally) and 17 missing, a total of 105. "I have never seen regular troops that equaled the Highlanders in soldierly bearing and appearance," commented General Sherman on the 79th's performance.

On 12 March 1863, Stevens was posthumously confirmed major general to rank from 18 July 1862. After the war, the surviving members of the 79th sent the same blood-stained flag, for which he given his life, to his widow.

Remainder of 1862

editDuring the Maryland Campaign of September 1862, the 79th saw action at the battles of South Mountain and Antietam. During the latter battle, the Highlanders fought near Burnside's Bridge and were deployed as skirmishers leading an advance along the Sharpsburg Road near the Sherrick House. Despite heavy Confederate fire, they pressed on, managing to drive in part of Jones' Division and capturing a battery of artillery. However, the arrival of A. P. Hill's troops drove the 79th back into the suburbs of Sharpsburg, where they engaged in a vicious firefight around the Sherrick House. In spite of heavy fighting, the regiment escaped relatively lightly with only 40 men killed, missing or wounded.

Following Antietam, the regiment saw duty in Maryland, and in December took part in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

1863

editThe 79th participated in the ill-fated "Mud March" of January 1863.

In February, Colonel Farnsworth resigned his commission as a result of the wounds he had received at Second Bull Run, and Lt. Col. David Morrison, who had been in command since 1 September 1862, was promoted to Colonel from 17 February.[7]

The regiment, as part of the 9th Corps, joined the Army of the Ohio in April and two months later was assigned to the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, of the Army of the Tennessee preparatory to joining the Vicksburg Campaign. They travelled by side-wheel steamer down the Ohio River, which was described as being of such shallow draft "it could sail on a heavy dew", and broke their journey at Louisville to spend a riotous couple of nights in the town's bars and "parlour houses", a euphemism for brothels, before arriving at the front.

A few days later, as Sherman rode down his column, on the march towards the town of Jackson, he was startled to be greeted by a loud cheer. Knowing his men were not usually so demonstrative he looked around to see who was showing such uncharacteristic enthusiasm. He saw the 79th New York newly arrived to join his unit. The last time they had met was in the camps around Washington after 1st Manassas when the fresh recruits had been roundly cursing him. Matured into veteran soldiers, they could now appreciate Sherman's merits and were delighted to see their ex-brigade colonel.

The regiment was too late to take part in the Siege of Vicksburg, but instead was sent to Jackson to tear up rail tracks and destroy the Mississippi Central Railroad at Madison Station.

August found the regiment back once more with the Army of the Ohio, in time to take part in Burnside's campaign in East Tennessee, seeing action at Blue Springs, Lenoir and Campbell's Station.

Battle of Fort Sanders

editAt Fort Sanders (known by the Confederates as Fort Loudoun), Knoxville, the Highlanders helped inflict a massive defeat on Longstreet's troops. The position, a bastioned earthwork, was on top of a hill, which formed a salient at the northeast corner of the town's defences. In front of the earthwork was a 12-foot-wide ditch, some eight feet deep, with an almost vertical slope to the top of the parapet, about 15 feet above the bottom of the ditch. It was defended by 12 guns and, according to different sources, 250 or 440 troops, of which the 79th provided 120.

Longstreet ordered the brigades of Humphreys' Mississippians and Bryan and Wofford's Georgians, approximately 3,000 men, to make a surprise attack on the fort. The night of 28 November was bitterly cold as the Confederate troops quietly moved into position just 150 yards from the fort, but, in spite of their caution, the defenders overheard them and were prepared for the coming assault.

At first light, the Confederates began their attack, struggling through telegraph wire entanglements which the Federals had stretched between stakes a short distance in front of the ditch. In spite of this obstacle the Rebels managed to reach the ditch with relatively light casualties, but it was there that their problems began. They found that there were no scaling ladders with which to climb the slope up to the parapet and the situation was further aggravated by the ground being frozen and covered in sleet which caused the soldiers to lose their footing and fall. In spite of this, some men did manage to reach the top by climbing on the shoulders of their comrades and were able to place their colors on the parapet. There then followed vicious close quarter fighting during which First Sgt. Francis W. Judge of Company K, 79th NY, grabbed the flag of the 51st Georgia from their color bearer and, in spite of a concentrated and deadly fire, was able to return in safety with his trophy into the fort. Judge, who was born in England, was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his action.

Longstreet's men were eventually forced to retreat to the yells of "remember James Island" from the elated Highlanders. The 79th sustained only nine casualties out of a total Federal loss of 20 killed and 80 wounded. They had inflicted terrible punishment on the Confederates who lost 813 men, killed, wounded and missing.

1864

editIn January, the 79th was reinforced for about two months by the 51st New York Infantry and the 45th, 50th and 100th Pennsylvania Infantry, taking part in fighting at Holston River and Strawberry Plains. In April, the Highlanders rejoined the Army of the Potomac in time to fight at the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, being engaged in the assault on the salient known as the "Mule Shoe."

It was at Spotsylvania that the original Cameron Highlanders were to fight their last engagement. Again they faced Longstreet's hard fighting veterans and once more the 79th drove them from the field, losing five more men killed or mortally wounded in the fight. Their colonel, David Morrison, was wounded and command was passed to Captain Laing. As the regiment stood in line on the bloody battlefield, the men received the order for muster-out, their term of enlistment having expired on 13 May 1864.

End of the war

editThose veterans whose term of enlistment had expired returned to New York City, where they were discharged. Less than 130 of the regiment's original members were left. Those with unexpired service were sent to guard Confederate prisoners bound for Alexandria. These men were later formed into companies A and B, which formed the nucleus of the "New Cameron Highlanders" that Col. Samuel M. Elliott had received authority to recruit on 4 May. In November 1864, companies C and D, made up of new volunteers, were added to the regiment, and Company E joined in January 1865. A further company, F, was organised in the field from recruits received in March 1865.

The new regiment served at Cold Harbor, Bethesda Church, Petersburg, Weldon Railroad and Poplar Springs Church. In October, they were appointed provost guard of the 9th Corps, taking part in the Appomattox Campaign.

After Robert E. Lee's surrender, the regiment moved back to Washington and took part in the Grand Review of the Armies on 23 May 1865. It continued duties at Washington until the men were eventually mustered out of Federal service on 14 June 1865, whereupon the regiment returned to state militia status. Ladies of the New York Scottish Society sent new glengarries for the regiment to wear for their re-entry into New York City.

During the war, the 79th New York lost 198 killed, plus 304 wounded or missing, out of a total enrollment of 2,200.

Postbellum service

editAfter the war, the regiment reorganized into a state militia organization and in 1872 had a uniform change to conform with standards of the United States Army. For example, their 1872 jacket was an artillery jacket modified with a sporran cut out. The 79th New York Highlanders were finally disbanded in January 1876 due to reorganization of the New York State Militia but maintained a strong veterans organization well into the 20th century.

See also

editAffiliations, battle honors, detailed service, and casualties

editOrganizational affiliation

editAttached to:

- Mansfield's Command, Department of Washington, to June, 1861.[8]

- Sherman's Brigade, Tyler's Division. McDowell's Army of Northeast Virginia, to August 1861.[8]

- W. F. Smith's Brigade, Division of the Potomac, to October.[8]

- Stevens' Brigade, Smith's Division, Army of the Potomac (AoP), to October. 1861.[8]

- Stevens' 2nd Brigade, Sherman's South Carolina Expeditionary Corps, to April, 1862.[8]

- 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Department of the South, to July, 1862.[8]

- 2nd Brigade, 1st Division. IX Corps, AoP, to September, 1862.[8]

- 1st Brigade, 1st Division. IX Corps, AoP, to April, 1862.[8]

- 1st Brigade, 1st Division. IX Corps, Army of the Ohio (AoO), to June. 1863.[8]

- 3rd Brigade. 1st Division, IX Corps, Army of the Tennessee, to August. 1863.[8]

- 1st Brigade, 1st Division. IX Corps, AoO, to April, 1864.[8]

- 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, IX Corps, AoP, to September.[8]

- 1st Brigade, 1st Division, IX Corps, AoP to October, 1864.[8]

- Provost Guard. IX Corps, AoP to July, 186S.[8]

List of battles

editThe official list of battles in which the regiment bore a part:[8]

- Battle of Blackburn's Ford

- First Battle of Bull Run

- Battle of Lewinsville[1]

- Port Royal Expedition

- Battle of Secessionville

- Second Battle of Bull Run

- Battle of Chantilly

- Battle of South Mountain

- Battle of Antietam

- Battle of Fredericksburg

- Siege of Vicksburg

- Jackson Expedition

- Battle of Blue Springs

- Battle of Campbell's Station

- Siege of Knoxville

- Battle of Fort Sanders

- Battle of the Wilderness

- Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

- Battle of Cold Harbor

- Siege of Petersburg

- Second Battle of Petersburg

- Battle of the Crater

- Battle of Fort Stedman

Detailed service

edit- Duty In the Defenses of Washington, D. C. till 16 July. 1861.

- Advance on Manassas. VA, 16–21 July.

- Occupation of Fairfax Court House 17 July.

- First Battle of Bull Run, VA, 21 July,

- Duty In the Defenses of Washington till October.

- Reconnaissance to Lewinsville, VA, 25 September.

- Reconnaissance to Lewinsville, VA, 10–11 October.

- Little River Turnpike, near Lewinsville, 10 October.

- Bailey's Crossroads 12 October.

- Sherman's Expedition to Port Royal, SC, 21 October – 7 November.

- Capture of Forts Walker and Beauregard, Port Royal Harbor, SC, 7 November.

- Occupation of Bay Point 8 November to 11 December.

- Duty at Beaufort, SC, and vicinity till 1 June 1862.

- Expedition to Port Royal Ferry 1 January.

- Port Royal Ferry 1 January.

- Action at Pocatello, SC 29 May.

- Expedition to James Island, SC, 1–28 June.

- Battle of Secessionville 16 June.

- Evacuation of James Island and movement to Hilton Head, SC, 28 June – 7 July.

- Moved to Newport News, VA, 12–16 July

- Moved to Fredericksburg, VA, 4–6 August.

- Pope's Campaign In Northern Virginia 13 August – 2 September.

- Operations on the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers August 1327.

- Second Battle of Bull Run 30 August.

- Chantilly 1 September.

- Maryland Campaign 6–22 September.

- Battle of South Mountain 14 September.

- Battle of Antietam 16–17 September.

- Duty In Maryland till 11 October.

- March up the Potomac to Leesburg, thence to Falmouth, VA, 11 October – 18 November.

- Battle of Fredericksburg 12–16 December.

- "Mud March" 20–24 January.

- Moved to Newport News, VA, 13 March

- Rail move to Kentucky 20–28 March.

- Duty at Paris, Nicholasvllle, Lancaster, Stanford, and Somerset till June.

- Movement through Kentucky to Cairo, IL, 4–10 June;

- Moved Vicksburg, MS, 14–17 June.

- Siege of Vicksburg 17 June – 4 July.

- Advance on Jackson, MS, 6–10 July.

- Siege of Jackson 10–17 July.

- Destruction of Mississippi Central Railroad at Madison Station, MS 18–22 July.

- At Milldale, MS till 6 August.

- Moved to Crab Orchard, KY, 6–12 August.

- Burnsides' Campaign In East Tennessee 16 August – 17 October.

- Action at Blue Springs, TN 10 October.

- At Lenoir, TN till 16 November.

- Knoxville Campaign 4 November – 23 December.

- Action at Campbell's Station 16 November.

- Siege of Knoxville 17 November – 4 December.

- Repulse of Longstreet's assault on Fort Sanders 29 November.

- Operations in East Tennessee till March, 1864.

- Action at Holston River 20 January.

- Strawberry Plains 21–22 January.

- Moved to Annapolis, MD., March, 1864

- Campaign from the Rapidan to the James 3 May – 15 June.

- Battles of the Wilderness 6–7 May;

- Spotsylvania 8–12 May;

- Ny River 10 May

- Spotsylvania Court House 12–21 May.

- Assault on the Salient 12 May.

- Non-Veterans left front, veterans left for New York 13 May.

- Non-Veterans guard prisoners to Alexandria, VA., 13–16 May

- Veterans moved to New York and mustered out 31 May. 1864.

- North Anna River 23–27 May.

- Totopotomoy 28–31 May.

- Cold Harbor 1–12 June.

- Bethesda Church 1–3 June.

- Before Petersburg 16–18 June.

- Siege of Petersburg 16 June 1864, to 2 April. 1866.

- Mine Explosion. Petersburg, 30 July 1864.

- Weldon Railroad 18–21 August.

- Poplar Springs Church 29 September 2 October.

- Boydton Plank Road, Hatcher's Run, 27–28 October.

- Fort Stedman 25 March 1865.

- Appomattox Campaign 28 March – 9 April.

- Assault on and fall of Petersburg 2 April.

- Occupation of Petersburg 3 April.

- Pursuit of Lee 3–9 April.

- Surrender of Lee and his army 9 April.

- Moved to Washington. D. C, 21–28 April.

- Grand Review 23 May.

- Duty at Washington, D. C, till July.

- Mustered out 14 July. 1865.

Casualties

editThe regiment lost a total of 188 men during service; 3 Officers and 116 Enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 1 Officer and 78 Enlisted men by disease.[9]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 5, p. 167-184.

- ^ Newton (2001), p. 120.

- ^ Dyer (1908), p. 271.

- ^ Todd (1886), p. 203.

- ^ Todd (1886), p. 212.

- ^ Gannon (1999), p. 116-121.

- ^ Todd (1886), p. 492-493,

- Roster of Officers - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Dyer (1908).

- ^ a b c d e f Dyer (1908), p. 1436.

Sources

edit- Dyer, Frederick Henry (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (PDF). Des Moines, IA: Dyer Pub. Co. pp. 29, 43, 193, 271, 273, 277, 314, 317, 318, 362, 363. 522, 538, 1435. ASIN B01BUFJ76Q. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Gannon, James P. (1999). Irish rebels, Confederate tigers : the 6th Louisiana Volunteers, 1861-1865. Campbell, CA: Savas Pub. Co. pp. 116–121. ISBN 978-1-882810-16-1. OCLC 191121989.

- Newton, Michael Steven (2001). We're Indians Sure Enough: The Legacy of the Scottish Highlanders in the United States. Auburn, NH: Saorsa Media. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-9713858-0-1. OCLC 51936872. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- Todd, William (1886). The Seventy-ninth Highlanders, New York Volunteers in the War of Rebellion, 1861-1865. Albany, NY: Press of Brandow, Barton & Co. LCCN 02014985. OCLC 276864900.

- U.S. War Department (1881). Operations in Maryland, Northern Virginia, and West Virginia. Aug. 1, 1861 – Mar 17, 1862. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. V–XIV. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 17, 165, 168–172, 174–177, 216, 561. hdl:2027/coo.31924077730194. OCLC 857196196.

External links

edit- New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center - Civil War - 79th Infantry Regiment History, photographs, table of battles and casualties, newspaper clippings, and national color for the 79th New York Infantry Regiment.

- [1] Cameron Highlanders of the Northwest website.

- 79th New York Volunteer Infantry on Electric Scotland