The amyrins are three closely related natural chemical compounds of the triterpene class. They are designated α-amyrin (ursane skeleton),[3] β-amyrin (oleanane skeleton),[4] and δ-amyrin. Each is a pentacyclic triterpenol with the chemical formula C30H50O. They are widely distributed in nature and have been isolated from a variety of plant sources such as epicuticular wax. In plant biosynthesis, α-amyrin is the precursor of ursolic acid and β-amyrin is the precursor of oleanolic acid.[5] All three amyrins occur in the surface wax of tomato fruit.[6][7] α-Amyrin is found in dandelion coffee.[citation needed]

α-Amyrin

| |

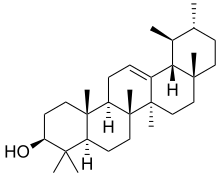

β-Amyrin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

α: (3β)-Urs-12-en-3-ol

β: (3β)-Olean-12-en-3-ol δ: (3β)-Olean-13(18)-en-3-ol | |

| Other names

α: α-Amyrenol; α-Amirin; α-Amyrine; Urs-12-en-3β-ol; Viminalol

β: β-Amyrenol; β-Amirin; β-Amyrine; Olean-12-en-3β-ol; 3β-Hydroxyolean-12-ene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C30H50O | |

| Molar mass | 426.729 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | α: 186 °C[1] β: 197-187.5 °C[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

A study demonstrated that α,β-amyrin exhibits long-lasting antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties in 2 models of persistent nociception via activation of the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 and by inhibiting the production of cytokines and expression of NF-κB, CREB, and cyclooxygenase 2.[8]

References

edit- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 653

- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 654

- ^ Saimaru, H; Orihara, Y; Tansakul, P; Kang, YH; Shibuya, M; Ebizuka, Y (2007). "Production of triterpene acids by cell suspension cultures of Olea europaea". Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 55 (5): 784–8. doi:10.1248/cpb.55.784. PMID 17473469.

- ^ Tansakul, P; Shibuya, M; Kushiro, T; Ebizuka, Y (2006). "Dammarenediol-II synthase, the first dedicated enzyme for ginsenoside biosynthesis, in Panax ginseng". FEBS Letters. 580 (22): 5143–9. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.044. PMID 16962103. S2CID 20731479.

- ^ Babalola, Ibrahim T; Shode, Francis O (2013). "Ubiquitous Ursolic Acid: A Potential Pentacyclic Triterpene Natural Product" (PDF). Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2 (2): 214–222. ISSN 2278-4136. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ Yasumoto, S; Seki, H; Shimizu, Y; Fukushima, EO; Muranaka, T (2017). "Functional Characterization of CYP716 Family P450 Enzymes in Triterpenoid Biosynthesis in Tomato". Frontiers in Plant Science. 8: 21. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00021. PMC 5278499. PMID 28194155.

- ^ Bauer, Stefan; Schulte, Erhard; Thier, Hans-Peter (2004). "Composition of the surface wax from tomatoes II. Quantification of the components at the ripe red stage and during ripening". European Food Research and Technology. 219: 487–491. doi:10.1007/s00217-004-0944-z. S2CID 90472894.

- ^ Simão da Silva, Kathryn A.B.; Paszcuk, Ana F.; Passos, Giselle F.; Silva, Eduardo S.; Bento, Allisson Freire; Meotti, Flavia C.; Calixto, João B. (August 2011). "Activation of cannabinoid receptors by the pentacyclic triterpene α,β-amyrin inhibits inflammatory and neuropathic persistent pain in mice". Pain. 152 (8): 1872–1887. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.005. ISSN 0304-3959. PMID 21620566. S2CID 23484784.